Streaming (1)

Sinopsis(1)

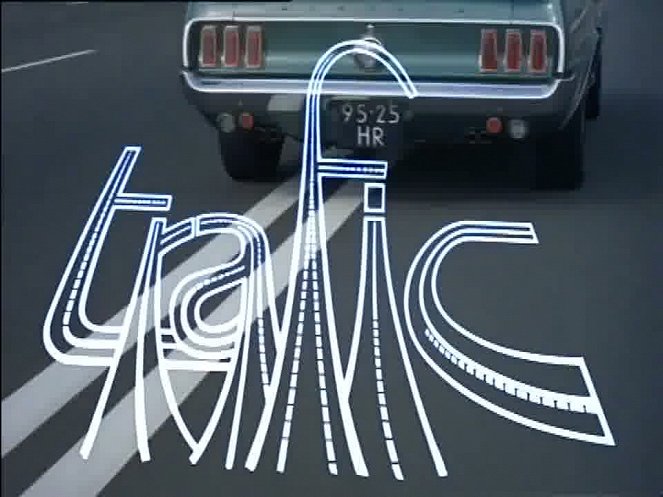

In his latest incarnation, Hulot is a vehicle designer at the Parisian firm Altra. Having recently completed the prototype for a Rube Goldberg mousetraplike ultraconvenient camper van, Hulot and Altra's pesky public relations girl, Maria (Maria Kimberly), embark to bring their newest creation to an auto show in Holland. The eagle eye of Tati's airtight humor follows Hulot on his doomed path to Amsterdam; he runs out of gas, has various accidents and engine difficulties, and invokes the wrath of both the police and customs officers. Interspersed between gags are seemingly documentary visions of French motorists picking their noses, being mimicked by their own windshield wipers, and generally causing trouble. (texto oficial de la distribuidora)

(más)Reseñas (1)

In order for this film to be made at all, Tati had to promise the producers that 1) he would again play Monsieur Hulot (a character forced on him by external circumstances), 2) he would pull Hulot out of the gaggle of extras and put him out front and, in connection with that, 3) this time he would not test the viewers’ attentiveness and would shift the focal point closer to the camera. After the financial disaster called Playtime, his last film over which he actually had full creative control, he had no other choice. Despite the above-mentioned restrictions, Traffic is effective slapstick that tastefully satirises the almost intimate relationship between a man and an automobile. One of the several ambiguous gestures (the man kneeling in front of the open hood) raises motoring to the level of a religion whose shrines are thus various trade fairs and car shows. Tati was fortunately able to retain enough creative control that he didn’t have to tell a complete story this time. The plot can be fully summarised with a simple sentence: Monsieur Hulot goes to an exhibition. As in slapstick generally, the determining (meaning-making) factor isn’t causality, but the interaction between the characters and the setting. Tati plays with the blending of the animate and the inanimate to the point of absurdity when he becomes an immobile part of a family house’s “living” vegetation. The cars are similarly animatedly inanimate, as their simple movement sets the main tone of the geometric symphony in motion, which paradoxically becomes really interesting only after a pile-up, when people have to get out of their substitute bodily shells (extensions of their senses, as McLuhan would write) and start improvising. There aren’t as many well-thought-out scenes in this film as in Playtime, some shots are only filler and not even the critical targeting of Traffic can be compared to that of Tati’s previous films. However, it is entertainment that, in its better moments, exhibits the touch of a genius, a man who thought with his body and spoke through his film, and who bid adieu to the big screen with one of the cleverest scenes of his career. Hulot’s rain gear finally starts to make sense after it starts raining. The attributes that define the character are exhausted by their use, and so is the idea of Monsieur Hulot. There is nothing more to add. 75%

()