Reseñas (862)

Peter Pan (1953)

A typical product of Disney’s classic era, with a lot of gratuitous clowning and making faces, butchering of the imaginative source work into a conservative narrative, which from today’s perspective is at the very least problematic (with respect to racism and gender issues) in many of its motifs.

Los ojos del bosque (1980)

Though Disney has always been synonymous with non-confrontational and conformist family entertainment, we can find in its rich history sporadic cases when the studio’s management approved a project that went in a distinctive direction. Unfortunately, however, the studio has treated most such titles like red-headed stepchildren, having them reshot or re-edited, or simply refusing to release them or allow a director’s cut to be made, despite the pleas of fans. The brilliant The Watcher in the Woods shares this fate with films such as Return to Oz, Something Wicked This Way Comes and Dragonslayer. The Watcher is a unique attempt at a children’s horror movie with fantasy elements and it is necessary to add that it was made a few years before E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and the birth of Amblin Entertainment and the associated boom in horror- and fantasy-style adventure movies that characterised children’s film production in the 1980s. However, this adaptation of Florence Engel Randall’s novel of the same name differs from all of the films that came after it in that it is a pure-blooded horror movie that crystallises into a children’s narrative only in the climax, whereas those other films transfer horror props or effects into the children’s genre with all of its stylistic rules. Like the masterful horror movies of the time, The Watcher in the Woods carefully builds its atmosphere using supernatural motifs suggestively rendered by means of its cinematography, editing and music, with only a minimum of special effects – especially Alan Hume’s camerawork gets under the viewer’s skin with its creeping movements and optical emphasising of the space. After all, the narrative itself rather exhibits the techniques of classic horror movies with elements such as an ominous house in the middle of a forest, mysterious events and the evident predestination of the main character, who bears a striking resemblance to the missing daughter of the house’s owner. The aforementioned ending is thus all the more surprising, as it actually negates everything that came before it, though that is rather more the fault of the studio, which did not give the director the option of creating a more complex climax as was originally intended. Nevertheless, even in its existing form, the film still remains a unique work and proof that it is possible to create a horror atmosphere without any bloody scenes, monsters, acts of aggression or a direct threat. On the contrary, it’s enough to have a continuously intensified mystery and a suggestive form.

Una pandilla alucinante (1987)

The 1980s were a golden age of children’s movies that gave their audience exactly what they wanted. It was a time when it was not only still possible to scare children (filmmakers weaned on eighties movies are breaking through the sterility of today), but everyone knew the kids were watching sci-fi and horror movies anyway, particularly the classic flicks from the fifties that were regularly rerun on American television. Accordingly, the new generation of films, of which E.T. was just the beginning, brought forth epic adventures with a touch of the fantastical and supernatural. The Monster Squad was made at a time when most of the now classic titles of the category and their variations were already in existence. As they were able to lean on those existing works, screenwriters Fred Dekker and Shane Black created both a full-fledged contribution to the genre of 1980s family adventure movies and an exaggerated reflection of them. After all, what more could ’80s kids want than to come face to face with popular classic monsters after the movies had already given them encounters with aliens, quests for pirate treasure and young versions of famous heroes. The film’s premise thus marches out a parade of all-star monsters – specifically Dracula, a werewolf, a mummy, the creature from the Black Lagoon and Frankenstein’s monster – connected with a conglomeration of canonical elements such as the hunt for a treasure in the form of a magical amulet, haunted houses, creepy neighbours and disintegrating families, and a secret boys’ club (with a regulation composition of an ardent nerd, a fearful fat kid, a self-confident chatterbox, an older cool guy, a half-pint no one listens to, and a little sister who has them all wrapped around her finger). In the interest of containing as many child-obliging motifs as possible, the narrative is conceived as a chain of loosely connected episodes that play with the usual conventions, and just as the film as a whole frees itself from a strictly fixed narrative, the individual sequences are surprising with their exaggeration and self-reflection (in most such films, the kids have a dog, but no one concerns themselves with how it gets into the treetop clubhouse). As suggested by the intermezzo in the form of mandatory school attendance between the breakneck adventures, the children’s world is conceived here as a place of absolute freedom, which inevitably seeps into those parts of the day when adults try to restrict it. Accordingly, the main strength of The Monster Squad is that it does not restrain itself with a rational point of view, but instead throws its viewers into a whirlwind of attractions that will put an enthusiastic, childlike smile even on the faces of adults who haven’t yet become completely jaded.

Scenes from the Suburbs (2011)

The short film Scenes from the Suburbs is an imaginative audiovisual supplement to Arcade Fire’s album The Suburbs. Actually, we can say that the combination of this film, the album and the music video for its lead single, which contains a number of extra shots not seen in the film, and the movie poster comprises a multimedia project that brings viewers and listeners a stirring melancholic impression of a world that has much in common with our own, but mainly engulfs viewers in the diverse, exuberant feelings associated with growing up and nostalgically looking back on that time in one’s life from the perspective of adulthood. The film’s premise literally realises the album’s expressive lyrics, thus bringing forth a kind of alternate reality in which individual suburban neighbourhoods function as separate military-controlled states separated by secured borders. This environment, where moving to another neighbourhood means the end of existing friendships and relationships, is the setting of a retrospective narrative that shows glimpses of the experiences of a group of adolescent friends during one fateful summer. The introductory monologue of the narrator, who says that he remembers only certain things and unfortunately not others, foreshadows the fact that the audience will not see the whole story, but only glimpses of it, from which we will not know exactly what happened, but we will feel the full emotional impact of the events and the changes in the characters. In the hands of Spike Jonze, this concept has been transformed into a captivating and intoxicating work that brilliantly expresses not only the carefree and excited emotionality of youth, but also the weight and pain of the inevitable end that comes with adolescence. Furthermore, all of this is set in a superbly melancholic world that is contemporary, fantastical and retro in equal measure – the film’s creators acknowledge that they were inspired by the films of Terry Gilliam, 1980s children’s movies such as E.T. and The Goonies, as well as the generational cult movie/guilty pleasure Red Dawn.

Donde viven los monstruos (2009)

Where the Wild Things Are is a grandiose film adaptation of the picture book of the same name by Maurice Sendak, which ranks among the classic works of English literature for children. Whereas Milne’s internationally acclaimed Winnie the Pooh is based on the character of an external adult narrator who tells Christopher Robin stories in which the latter’s toys and animals from the area take on distinctive personalities, Sendak provides direct insight into the minds and imaginations of children. This does not take the form of colourful imbecility, which many creators of children’s books and films imagine under the combined banner of childhood and fantasy, as it shows the qualities of children that are usually absent in other works due to idealisation – uncontrollability, capriciousness, sulkiness, self-centredness and the need for constant attention from others and a supply of new stimuli to amuse them. The film adaptation, directed by Spike Jonze, required expansion of the 27-page book in order for it to work as a feature-length film. Therefore, greater focus was placed on the characters in a fantasy world similar to that of the Winnie the Pooh stories. Sendak’s story about a young boy who, after a quarrel with his mother, runs away into a fantasy world where he becomes the king of scary wild creatures showed fantasy purely as a space that is literally subject to the whims of the hero. Jonze and co-screenwriter Dave Eggers gave the originally nameless creatures distinctly individual personalities that mirror different parts of the boy’s own personality and the attitudes of the people around him. Paradoxically, the space to which the boy has run away from the outside world becomes a place where he is confronted with himself and how he treats others and how others treat him. The film thus gently introduces into the original narrative about childhood elements of adolescence as a phase of life when we begin to realise that we are part of a society in which we have a certain position and that we must subordinate our behaviour to our relationships with other people. Thanks to that, the film is not just another naïve “celebration of children’s imagination”, but rather an accurate view of childhood, which, like the wilderness portrayed in the film, contains affection, danger, merriment, anxiety, creative joy and self-indulgent destructiveness.

Citizen Steve (1987)

This over-the-top documentary and tribute to Steven Spielberg on the occasion of his fortieth birthday is entertaining with its Citizen Kane stylisation. Oddly, however, viewers who are eager to learn about a man whose visual creativity fascinates millions of moviegoers will find more value in the stories told by the master’s friends and neighbours from the time of his adolescence than from the stilted stylised testimonials from the stars of the film industry.

Los niños no deben jugar con cosas muertas (1972)

Bob Clark was one of the first directors to pick up the gauntlet thrown down by George Romero, who not only fundamentally transformed the canon of pop-culture zombie mythology, but mainly used the walking dead as a catalyst for social criticism. Clark focused primarily on the latter aspect, so rather than horror, he presents a biting satire in which the zombies appear at the end as a form of divine, or rather infernal intervention. Unfortunately, the rest of the film conversely focuses on a heavily thesis-based and stiff depiction of the dynamics within a group of hippie bon vivants. As such, Clark and Alan Ormsby’s screenplay presents a caustic picture of the hippie community in the era of its decline, revealing that the internal workings of that group are subject to the same social pressures and power struggles as in mainstream society. Besides naïve and crazy people, the group is also composed of cynics, materialists and manipulators, with a charismatic leader standing at the centre of everything, though he gradually proves to be not only a manipulator and egocentric, but mainly his own construct, desperately trying to build a cult of his own personality and whose flowery speech conceals his calculating nature and systematic efforts to hide his own insignificance and pitifulness. Unfortunately, everything said in the film is delivered in an extremely stiff manner. Perhaps thanks to that, on the other hand, the excellent staging and dramatic elements shine through even more, particularly the final sequence, during which even the corpses themselves seem to marvel at the central character’s spinelessness.

Ghost Town (1988)

A futile attempt – even the most imaginative premise loses its appeal when it’s handled in an entirely routine manner. Ghost Town is exemplary video trash from the second half of the 1980s in that it has a perfect poster and a promising concept, but the film itself doesn’t contain anything memorable. After all, the concept of a zombie western may seem like a great idea, but in the late ’80s, when zombies had become a dominant element of pop culture (as had been confirmed and reinforced by the video for Michael Jackson’s “Thriller”), there were dozens of films in which the living dead take on countless bizarre forms (see crazy genre mish-mashes like Return of the Living Dead, Dead Heat, Night of the Creeps, The Video Dead, The Boneyard and The Vineyard). In other words, a concept alone is not enough, as it is necessary to also think about how it’s going to be executed. In the case of Ghost Town, this remains on the level of a formulaic genre flick, albeit a solidly crafted one. The inner meaning of the film thus appears to be much more interesting than the whole storyline with zombies and the mystery of the titular ghost town. The story of a small-town cop who, when on the trail of a marriage scammer in the desert, falls into some sort of parallel dimension in which he has to take on the role of the sheriff who will definitively eliminate the living dead in the cursed town, basically and literally represents the dream of every redneck cop who in his everyday boredom fantasises about a grand western adventure in the style of the movies that inspired him to be a cop in the first place.

SheZow (2012) (serie)

An animated series for children in which traditional gender roles are criticised, reflected on and ridiculed in a way that is passed off as playful entertainment. This isn’t an analysis of the subliminal level, but a description of the very top layer of the work. After all, this is indicated by the series’ premise, in which a boy turns into a legendary superheroine. Besides the regular situations when he is supposed to act like a girl or resist doing so, or try not to reveal his identity to his friends, one of whom is in love with the superheroine, there are also a number of references to and reflections on the way superhero stories and identities work.

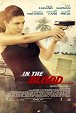

Venganza (2014)

Gina Carano obviously deserves roles in films with significantly bigger budgets than this one. Nevertheless, the fact remains that she will never get a leading role in Hollywood, because she does not fulfil the physical criteria imposed by Tinseltown producers. It is not a coincidence that she was given her first leading role, in Haywire, by genre provocateur Steven Soderbergh, who is one of harshest critics of the Hollywood system. Unfortunately, we can only expect her future career path to continue with respectable supporting roles in top-tier productions and leading roles in straight-to-video B-movies. In the Blood is nothing to be ashamed of; on the contrary, it is a film that surprisingly brings honour to its star. Despite the mistaken expectations of some fans, this tropical variation on Taken does not offer a whirlwind of action scenes, but rather a thriller focused on the main character advancing through various constituent revelations. It’s true that In the Blood is far from being a match for the aforementioned French-made masterpiece in terms of dramaturgical cohesiveness and the dynamism and intensity derived from the settings in which the protagonist operates. On the other hand, however, the concept of reversing the standard gender roles in action movies brings a certain freshness to the film in that it gives the character the possibility to not just be a run-of-the-mill killing machine, but to also occasionally show a human side. Thanks to this, and of course to Gina Carano’s charisma and physical presence, we have here a welcome alternative to ridiculously testosterone-fuelled B-movies. This overall concept is marked by the limitations of the action scenes and their execution in a chaotic style that denies viewers the usual visual pleasure of action money shots and instead focuses on depicting effectiveness, but without presenting the character’s fighting ability as her sole defining trait. Thanks to the fact that the film does not define its protagonist only as an action object (and other elements such as the romantic introduction), it can be said that something particularly unique has been created – an action film for women in which even the viewer’s usual roles of worshipful admiration and active projection of themselves onto the character are also reversed.