Reseñas (863)

Venganza (2014)

Gina Carano obviously deserves roles in films with significantly bigger budgets than this one. Nevertheless, the fact remains that she will never get a leading role in Hollywood, because she does not fulfil the physical criteria imposed by Tinseltown producers. It is not a coincidence that she was given her first leading role, in Haywire, by genre provocateur Steven Soderbergh, who is one of harshest critics of the Hollywood system. Unfortunately, we can only expect her future career path to continue with respectable supporting roles in top-tier productions and leading roles in straight-to-video B-movies. In the Blood is nothing to be ashamed of; on the contrary, it is a film that surprisingly brings honour to its star. Despite the mistaken expectations of some fans, this tropical variation on Taken does not offer a whirlwind of action scenes, but rather a thriller focused on the main character advancing through various constituent revelations. It’s true that In the Blood is far from being a match for the aforementioned French-made masterpiece in terms of dramaturgical cohesiveness and the dynamism and intensity derived from the settings in which the protagonist operates. On the other hand, however, the concept of reversing the standard gender roles in action movies brings a certain freshness to the film in that it gives the character the possibility to not just be a run-of-the-mill killing machine, but to also occasionally show a human side. Thanks to this, and of course to Gina Carano’s charisma and physical presence, we have here a welcome alternative to ridiculously testosterone-fuelled B-movies. This overall concept is marked by the limitations of the action scenes and their execution in a chaotic style that denies viewers the usual visual pleasure of action money shots and instead focuses on depicting effectiveness, but without presenting the character’s fighting ability as her sole defining trait. Thanks to the fact that the film does not define its protagonist only as an action object (and other elements such as the romantic introduction), it can be said that something particularly unique has been created – an action film for women in which even the viewer’s usual roles of worshipful admiration and active projection of themselves onto the character are also reversed.

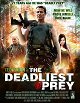

Deadliest Prey (2013)

Rather than a proper sequel, Deadliest Prey is both a remake of and an adoring tribute to the legendary trash flick Deadly Prey. More than two decades after its initial release, the classic bumbling opus by the undiscerning autodidact David A. Prior and his steroid-guzzling brother Ted Prior is now considered to be a cult artifact. Furthermore, the generation of his admirers who discovered him on VHS as teenagers is now of productive age, enabling David to fully fund his adolescent obsessions. Thanks to those admirers, the Prior brothers willingly returned to their greatest and – let’s be honest – only famous title and they set out to exploit their revived fame in the spirit of Stallone’s The Expendables. The original Deadly Prey was made basically as an enthusiasts’ project by a group of friends, which incidentally received backing from the trash factory Action International Pictures, and the new film is also the equivalent of a community-theatre production made by the original group in collaboration with their admirers for all of the ardent fans of Deadly Prey. If we leave aside the passages with the honorary roles for the enthusiast producers (A. Wade Miller and Fabio Soldani) and the group of film nerds who were instrumental in reviving or rather for establishing the cult of the Priors (Dimitri Simakis of Everything is Terrible! and Zack Carlson of the Alamo cinema), the film is composed exclusively of passages that copy, paraphrase or reference identical sequences in the original film. At its core, Deadliest Prey is thus an attempt to step into the same river a second time, which on the one hand simply gives fans exactly what they want, but at the same time we can also caustically observe it as evidence of the fact that David A. Prior has not in any way advanced in his creative career. He continues to shoot films using the disarming absolute frame technique, where the characters see nothing beyond the boundary of the camera shot, so we again enjoy a number of shots that should have ended a second or two earlier instead of just leaving the actors blankly staring into space after saying their lines. Of course, the main attraction is the return of the old ensemble, particularly Ted Prior, who at least looks relatively good for his age despite having lost his iconic mullet, though unfortunately also David Campbell, who has severe motoric problems and on whom alcohol has taken an obvious toll, and even Fritz Matthews appears as the killer Thornton, who seems to have gained two hundred kilos. In addition to the spectacular entertainment at the expense of the creators in terms of amateur acting, dismal craftsmanship, blatantly edited-in effects, would-be tough-guy lines and, of course, loads of satisfying allusions to the iconic moments of Deadly Prey, the Priors’ comeback is surprising with several moments of unintended self-reflection. The most telling of these is the scene in which Danton tells his son that he’s sorry that he dragged him into his problems, whereas in real life, this is what the worn-out Ted Prior says to his real son, who, together with his uncle David, was forced to participate in another chapter in the curse of the Prior family as mercilessly ridiculed bunglers who are condemned to eternally run around in the woods and play soldiers with replica rifles.

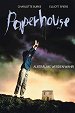

La casa de papel (1988)

Paperhouse is based on the brilliant idea of depicting the line between childhood and adolescence through children’s drawings. The film does not take these drawings as primitive records of reality, but rather as a faithful depiction of imagination. The narrative is about an adolescent girl who in puberty begins to define herself against everything and everyone, but her drawings, among other things, indicate that at heart she is still a child who does not perceive her actions causally, but only egocentrically. Her adolescence thus unfolds through her gradual acceptance of responsibility and awareness of the consequences of her caprices. The girl is troubled by feverish dreams, during which she finds herself in the literally real world of her drawings. This time, however, the fantasy is not formed according to the her ideas, but actually defies her with its consistent logic that everything materialises within it, though everything is exclusively what she draws into it. When the girl tries to subjugate this world and childishly rebel against it, she falls into increasingly bizarre and terrifying visions. Paperhouse is fascinating due to its original premise (adapted from the novel Marianne Dreams by Catherine Storr) and its ambition to show the transitional period of adolescence as an ambiguous and essentially traumatising experience, which is expressively conveyed through the simple and warped production design.

Oz, un mundo fantástico (1985)

Whereas some of the celebrated children’s movies that have become cult classics, such as The Peanut Butter Solution, now exhibit certain dramatic stumbles and it is necessary to squint one’s eyes to bring their loosely structured narratives into focus, Return to Oz is a perfect film that has not aged at all and is still able to draw in and captivate even adult viewers. In terms of craftsmanship, it is a refined work with flawless mechanical effects and an enchanting atmosphere that combines awe-inspiring fantasy with unsettling elements to create multiple meanings. This is due in part to the perfect Fairuza Balk, whose distinctive performance gives Dorothy a liveliness that transitions seamlessly between immediacy, timidity and childlike determination. In addition to that, the film is a phenomenal work in the context of the Wizard of Oz “franchise”, as it flawlessly bridges the gap between L. Frank Baum’s original vision and the bastardised canon established by the uncritically accepted canonical film adaptation from 1939. On the one hand, the narrative of Return to Oz is related to that of the old film, but instead of vaudevillian playfulness, it brings the world of Oz back to the darker and more unsettling form that Baum constructed in his books (which was preserved in the 1982 Japanese-American animated adaptation), while also brilliantly combining motifs from the second and third instalments of Baum’s book series into one distinct narrative. However, the screenplay does not literally follow on from the classic film, or more precisely, its primary meaning, where Dorothy adopts the conservative view that home is the best place to be. On the contrary, it is based on a subversive reading in which the trip to Oz is interpreted as a manifestation of the protagonist’s nature, which she must hide from those around her. Therefore, at the beginning of this sequel, Dorothy’s aunt takes her to a doctor to rid her of her fixations. When Dorothy gets back to the world of Oz after the anxiety-inducing introduction in the mental hospital, it’s not an escapist return to a colourful realm, as the Emerald City is in ruins and her friends have been turned to stone. The premise brings back to the world of Oz the danger that the creators of the old saccharine musical eliminated from Baum’s book. At the same time, it also opens up the central motif of Return to Oz, which is that Dorothy has to fight for her imagination and defend it against the selfish people around her – though not directly and actively, but simply by not letting herself be intimidated and by facing the obstacles and dangers with which she is confronted (which again corresponds to Baum’s books). In accordance with that, all of the characters that she meets, whether they join her as her guides or stand in opposition to her, are characterised by grotesque ambiguity and the individual peripeteias are rather bizarrely fantastical in the sense that they have their own logic and defy the usual ways of thinking about the real world (see the role of the hen, the form of Princess Mombi and the revived Gump). In every respect, Return to Oz is a brilliant work that ranks alongside the best children’s films, such as The NeverEnding Story and Hook, which do not approach the theme of childhood and imagination in a superficially naïve way. In its time, however, Return to Oz unfortunately ran up against the stubborn obtuseness of both viewers and publicists, who associate The Wizard of Oz only with the film and not the book and demanded another lobotomising musical. In contrast to that, Return to Oz is a flawless contribution to the trend of eighties children’s films that brilliantly combined adventure entertainment with darker tones and ambiguous motives, which was characteristic not only of the ambitious Amblin, but also of many other companies, including Disney, which, after all, funded Murch’s vision.

Cherry 2000 (1987)

Though Cherry 2000 has an entirely original premise involving a futuristic world in which sex has become an annoying matter of bureaucracy so that so love blossoms rather in relation to androids, it otherwise has too much in common with the meta-genre satire A Boy and His Dog, which was made twelve years prior and thus even before desert post-apocalyptic action flicks became one of the dominant genres of trash pop culture. In both films, the default McGuffin is the protagonist’s desire to get laid, most of the plot is set in the desert, the narrative shows various bizarre groups of people and bizarre forms of civilisation in the wasteland, and in each film the protagonist becomes an involuntary guest in a deranged community that looks like a dystopian version of a 1950s suburb with fake smiles, overblown gender archetypes and monstrous adoration of conformity. However, the two films are fundamentally different from each other in that, while in the earlier film the protagonist is accompanied on his journey by a hyper-intelligent dog, in Cherry 2000 his guide is a fearless warrior and smuggler played by Melanie Griffith, though their roles in the narrative, especially in the final point, are basically identical. But because of this shift, Cherry 2000 becomes a run-of-the-mill genre spectacle, unlike its unacknowledged inspiration. The only thing it retains from the sharp wit of A Boy and His Dog is its obvious use of the basic principle of post-apocalyptic films. The story of a man spoiled by big-city life who sets out into the wasteland, where he is transformed into a valiant warrior, literally shows that Mad Max and its countless imitators are nothing more than futuristic westerns that, instead of the unwanted effect of nostalgia for bygone romantic times, offer the heroically naïve promise of a future in which classic virtues return at full strength. Compared to traditionally macho visions of the post-apocalypse, it may seem that Cherry 2000 even perhaps offers a feminist version with a strong female protagonist. On closer inspection, however, it is apparent that even though E. Johnson comes across as a seasoned, fearless heroine in the beginning, that’s only because we are waiting for the male hero to cast off the pampered nature of modern civilisation and grow into the role of a classic tough guy during his later adventures. In addition to her timidity in taking the initiative with respect to getting closer to the hero, the heroine’s inner passivity is made complete by Melanie Griffith’s fragile voice, which is reminiscent of a woman from a kitschy melodrama from the 1950s. As a result, Cherry 2000 is actually a bastardisation of A Boy and His Dog. Instead of social satire and mockery of classic adventure genres, its narrative is transformed into a mediocre genre flick precisely in the spirit of 1980s post-apocalyptic westerns.

Callejón infernal (1977)

The talk about how Damnation Alley is a great cult sci-fi flick with souped-up effects that only languishes in the shadow of Star Wars, which was released only a few months before by the same studio, is very misleading. The creative brilliance of George Lucas and the revolutionary nature of his special effects are entirely evident when set side by side with Damnation Alley. If the sources on IMDb can be believed, even Star Wars cost less to make than Damnation Alley, where apparently a large part of the budget went into the production of fully functional futuristic vehicles, which the film doesn’t use as an attraction at all, and we only learn about the ingenuity of their construction from bonus interviews, but not from the film itself. Besides the rather poor and ridiculous visual effects, which are limited to re-colouring the sky in whole shots, the film’s fatal weakness is it’s mediocre screenplay and its undramatic execution in episodic sequences, which are basically interchangeable and have no meaning in the story as a whole. When we add to that characters who have no personality at all, then it’s really no wonder that Damnation Alley and its outdated effects didn’t hold up in comparison with Star Wars. But what’s really surprising is the existence of a handful of avowed fans who swear by this film.

Los goonies (1985)

The Goonies is deservedly considered to be a cult classic among adventure movies and the most illustrious representative of Amblin’s ’80s adventure flicks for kids, which situated spectacular, fantastical adventures in the mundane setting of American suburbs and small towns, and were conceived as rollercoaster rides packed with a full range of emotions, from suspense to fear and horror to rollicking fun.

Guerreros del sol (1986)

Solarbabies represents 1980s pop culture distilled down to its most concentrated essence. The foundation of the film consists in a narrative framework taken from high-school sports movies, except this time the peer relationships, sports matches and rebellions against authority are transplanted into a post-apocalyptic wasteland along the lines of Mad Max 2 (and its dozens of clones) with glimmers of new-age mysticism and eco-hippieism. In accordance with the fashion of the time, the main sport combines roller skating and lacrosse. And if that weren’t enough, there is also a kind alien who brings the central group together in the manner of E.T.; in fact, the whole film is conceived as an action-adventure family movie like the legendary The Goonies and other Amblin productions of the era. This post-modern mishmash is then populated with the purest character templates that could be carved out the conformist culture of the 1980s. Thanks to that, Solarbabies is a masterpiece of conservative manipulation that foists the traditional values of the white patriarchy on young viewers. Behind all of the breakneck adventure, there is thus a not very subliminal guide to life for white adolescent males, who are supposed to be the good guys and the leaders, while the girls serve as their emotional ornaments whom they must protect, in return for which they will receive a kiss; the black characters are fine guys who obey the white leaders unconditionally, and the Indians are an odd group living in harmony with the natural side of society.

Cuando el viento sopla (1986)

We can describe When the Wind Blows as Grave of the Fireflies with pensioners and a British temperament, which may give some vague idea of what to expect from the film, but it falls far short of describing its main qualities. The heart of the film is its premise based on the Raymond Briggs graphic novel of the same name, which deals with the themes of atomic warfare and nuclear holocaust through the lens of an ordinary retired couple living in the countryside, whose relationship has settled into the form of small rituals and accepted roles over their years of living together. These rituals and roles form the basis of their immediate response to the threat, which is so devastating that the characters cannot comprehend it in all its severity. In terms of concept, we can actually describe When the Wind Blows as an anti-war farce in which the traditional image of nuclear war is deconstructed by the ordinariness and humanity of the central pair of old-fashioned pensioners, who constantly and naïvely compare the new war with the one that they had survived and bounced back from in accordance with the dominant ideology. Nevertheless, bitter and depressing tones eventually begin to pierce the levity as the first signs of the direction that the old man’s fate will take start to come into focus. Even so, the film never superficially plays on emotions; rather, its impact is derived from contrasts and the viewer’s awareness of the consequences of things that the characters do not understand or do not want to admit.

Nintama Rantaró (2011)

Miike’s third contribution to the genre of children’s movies (after The Great Yokai War and Yatterman) clearly shows that the most productive of the current top Japanese directors understands children very well. Indeed, the melancholically conceived motifs relating to childhood and adolescence comprise one of the recurring elements across his varied filmography. This time, however, the adult perspective on childhood remains on the sidelines and everything is rather subordinated to a superficially childlike view. On the one hand, this means the lowest-brow jokes based on children’s fascination with poop, farts and other manifestations of human bodily functions at which parents take offence. As in a number of previous comic-book adaptations, Miike brings into Ninja Kids!!! various elements of comic-book stylisation, which this time leads to a slapstick exhibition of physicality. In accordance with the kids’ view of the world (and with the original manga), all of the adult characters (perhaps only with the exception of the main protagonist’s parents) have the form of caricatures with bizarrely deformed faces and expressively exaggerated facial features and other physical attributes (the ninja that looks like Robert Z’Dar is one of the more normal ones). Simply said, the film literally makes it clear that in the eyes of children, adults and old people in particular are bizarre monsters who speak strangely and fart constantly. And that’s not to mention the literal preservation of the characteristic comic-bookish appearance of the baseball-sized lumps that appear on the heads of characters who have taken a beating. Of course, the superficiality here does not imply the insipidness or dullness of the creators. On the contrary, with its disarming rendering, the film demonstrates the sincere interest and imaginativeness of Miike’s approach to filmmaking. Frequent sequences involving monologues, by means of which one character explains something to another or to the viewers, break up the silly jokes, while gratuitous variety-show gags are inserted into the plot sequences, and everything is subordinated to concise comic-book stylisation. When the character of the veteran ninja cuts through the background of a scene so that he can interrupt the action with a factographic explanation and then tells the heroes to tape it back together after him, which they do before the scene resumes – but the sequence just described is far from the most creative of the whole film. That honour goes to the captivating theatrical handling of the end of the race, when the actors run around on a rotating platform with papier mâché decorations. Even past the age of fifty and having established himself in the mainstream, Miike simply has not lost any of his creative distinctiveness, and especially among the works in his filmography of recent years, Ninja Kids!!! is a welcome departure.