Reseñas (935)

La noche es nuestra (2007)

From the first scene, it is clear that Bobby likes having matters in his own hands. That certainty, which sharply diminishes from the first plot twist (to the point of notably wandering through smoke), reflects the doubtfulness of the United States at the end of the 1980s. Though, in the spirit of the Cold War, the villains are Russians (Soviets), nationality ceases to be a determinative, distinguishing feature for the emerging multicultural melting pot. The important things are attitudes, politics and, in particular, relationships. Relationships within families and “families”. The law is an obstacle. Only two things connect Bobby with the much more scrupulous Joe: the authoritarian character of their father and religion. In order to find the way to his brother, Bobby has to reassess his attitude toward both. The primary attraction of We Own the Night is not one and a half action scenes, but rather the thought processes of the well-drawn protagonists. The actors and the confining environment that envelopes them make watching their change in behaviour an absorbing experience. Crime is everywhere around them; only tight-knit families are safe. From the film’s long sequences, you sense something bad coming and you know that what is supposed to happen is going to happen. This fatalistic “givenness” of everything that occurs gives the film elements of ancient tragedy, including suffering in slow motion. Only a few dim-witted moments have a detrimental effect on American mainstream attitudes to the notably slow, sad and penetrating crime story (a moment ago you were almost a drug dealer, but now we’ll let you be a cop, because you have to pay your debt). Otherwise, I recommend watching Gray’s preceding film, The Yards, which elaborates a similar theme and with its cast (Wahlberg, Phoenix) also has a lot in common with We Own the Night. 75%

Ready Player One (2018)

The best Easter movie. You won't find more Easter eggs anywhere else. In comparison with the book on which it is based, Ready Player One has more levels of meaning and a more concise narrative, and it makes more sense. The real and digital worlds are intertwined much more organically in the film than in the original work, which we become aware of thanks to the cuts from OASIS to Ohio at key moments of the narrative, and which Wade experiences with extraordinary intensity (astonishment, fear, love). The fluidity of the story is also aided by the smooth transitions between the two sub-worlds using sound bridges and compositionally similar shots. ___ Compared to the book, the film’s exposition is highly condensed, but we learn from Wade’s voiceover everything we need to know in order to understand the story (the message that people stopped solving problems and began pretending that they don’t exist is especially telling). We may not necessarily be interested in how OASIS works (or doesn’t work) in the rest of the world, because Wade, whose perspective the narrative adheres to at first, isn’t interested himself. We later set Wade aside a few times in favour of other characters, who are more multi-dimensional than in the book. ___ In order for the protagonist to stop seeing the search for the keys as entertainment and to start understanding its real consequences, a girl who has unsettled accounts with IOI is needed. Wade’s awakening occurs during a dance sequence, which may otherwise seem like a pointless diversion from the main story (however, i-R0k also reveals the true identity of Parzival). ___ Art3mis is not just a manic pixie dream girl and a prize to be won. The protagonist’s awakening depends on her. She is also the one who drags Parzival into reality, thanks to which we realise, much earlier than in the book (which moralises in an awkwardly appended epilogue), the conflict between the real and virtual worlds. The central idea better permeates the entire narrative and is excellently connected to the story of Halliday, who is also a much livelier character than in the original (for which, among other things, the phenomenal Mark Rylanek deserves credit). ___ The relationship with Halliday is even more important to the protagonist than his bond with Samantha. He accepted the genius inventor as his surrogate father, from whom he learns what is right and what is wrong in life. Like Spielberg’s other young protagonists (Elliot, Jim from Empire of the Sun, Frank Abagnale), he finds, thanks to someone else, a replacement for his dysfunctional/non-existent home, to which he cannot completely dedicate himself, because it simply isn’t real. ___ For many viewers, Spielberg himself is a similar father figure who creates worlds to which we can safely escape from incomprehensible reality. In Ready Player One, he offers us another such world, while warning us of the risk that it could completely (i.e. irreversibly) absorb us. At the same time, we should believe that one of the huge companies (Gregarious Simulation Systems), which is on Wade’s side, thinks about consumers, while the other (IOI) pursues only its own enrichment, in which lies one of the story’s main paradoxes. ___ For me, Ready Player One is primarily a movie about returns. Returning in time, returning home, returning from the virtual world to reality. In the first challenge, Parzival must shift into reverse; the second takes place within the space of a film about a man trapped in a time loop; to complete the third challenge, it is necessary to uncover the very first video-game Easter egg, thus revealing the creator’s name. The realisation that real people are behind the virtual world is the point of Halliday’s game. Only the person who knows the details of the creator’s life relating in a certain way to how he thinks (breaking the rules) or what he most regrets (the girl he didn't kiss, the friend he lost) can win. ___ Pop-culture references serve the narrative much better than in the book. This is not an autotelic service for nerds, though it is sometimes a bit unnecessarily pointed out to us that the motorcycle over there is from Akira. For example, as Wade’s race car in OASIS has a design similar to the DeLorean in Back to the Future (with accessories from Knight Rider’s KITT), we understand that he's a fan of Zemeckis’s sci-fi comedy and it thus makes sense when he purchases from a video-game store a “Zemeckis Cube”, which later helps him to escape from a difficult situation. Many of the songs refer to specific scenes from particular films (“In Your Eyes” from Say Anything…, “Also sprach Zarathustra” from 2001: A Space Odyssey), and if you’re in the picture, you will fully appreciate the extra layer that they add to the given moment of the film. Also, other products of the (predominantly) American entertainment industry not only serve as rewards for attentive viewers, but also convey the motifs that the film presents and help bring clarity to the story. ___ From a geek’s perspective, Ready Player One is visually, intertextually and technically so sophisticated that it touched me a few times and in the end I - at the same moment as Wade – even shed a tear (and I think that not being ashamed to admit something like that is the essence of geekdom). Even from a film critic’s perspective, I did not find any fundamental shortcomings in the film. Narratively, it is a brilliant affair without dead spots, the action scenes are extremely uncluttered (even in 3D), the story has many more layers than it may seem to a naive viewer... (though you don’t have to agree with its message like I do). In short, I don’t think that my almost uncritical enthusiasm derives only from the feeling that this is a film just for me (which is a feeling that millions of other viewers probably have). 90%

Holy Motors (2012)

“Weird … so weird.” The main prerequisite for understanding Holy Motors is to have a love for moving pictures and a willingness to let yourself be surprised and astonished. Carax’s film about films (and motion as such), actors (who can never completely abandon a role) and viewers (who, in the digital age with ubiquitous cameras, are also actors) begins when the still image was first set in motion (Étienne-Jules Marey). Subsequently, it offers a cross-section of film history and genres in an anti-narrative series of episodes linked together by Mr. Oscar (Carax’s birth name is Alexandre Oscar Dupont) as the personification of that motion (there is definitely a good reason that he is played by one of today's most talented actors) and a medium conveying meanings (his transformations are transformations of cinema as such). Social drama, anarchistic comedy (did Lavant’s imp also remind you of Chaplin?), gangster flick, musical, melodrama... The focus of Carax’s films has always been more on other films than on reality. Here he elevated this approach to the main principle of the narrative, resulting in a film composed of situations known from other films and thus deconstructing the film’s narrative. Unlike many of his colleagues who write love letters to cinema, however, Carax refuses to be sentimental or to consider that films and viewers are no longer what they used to be. His journey into the depths of one night in Paris (guided by a lady bearing the name of the famous French novelist, Céline) is subversive, cheeky and malevolent, as everyone must realise during the penultimate scene depicting the return to the “family” (and to the evolutionary origins, not of film, but of man – one cannot exist without the other). Beauty and weirdness are represented here in equal measure. Carax does not lament the end of film, but rather thinks about its possible rebirth. He understands film as a collective dream (in one of the first shots, we see a hall full of sleeping viewers). As a love affair (when the lovers in one of the last episodes talk about the fact that they have 30 minutes left, that also happens to the same amount of time remaining until the end of Holy Motors). Like life (we are all the sum of the films that we have seen). Life through films. Where there are no films, only death remains. P.S.: Holy Motors is also valuable educational material. In the imp segment, it shows the only appropriate reaction to a person who enjoys using “air quotes”. 90%

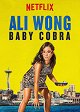

Ali Wong: Baby Cobra (2016) (programa)

Much more than men, women are expected to be congenial and orderly in all circumstances, to yield to the adjective “tender”, which is commonly associated with their gender. Most contemporary stand-up comediennes turn this supposition on its head. A case in point is Ali Wong, who through her performances draws attention to the reverse side of nice things and adds a dark undertone to outwardly innocent activities. For example, when she talks about how she likes to make a snack for her husband every day and then concludes with a conspiratorial remark that she does it so that he becomes dependent on her and never leaves her. The praise of a woman’s life in the household is based on a description of how at home you needn’t stress out about taking care of a major need in shared restrooms with thin, flimsy paper and nearby colleagues trying to dampen their bodily sounds. In describing bodily functions, Wong, like Amy Schumer, examines the issue down to the smallest detail with clinical matter-of-factness. Although she does not talk about human sexuality in a more scandalous manner than her male counterparts, many critics who consider such openness in the area of sexuality unacceptable for women have a problem with such comedy delivered by women. Whether Wong is talking about sex during pregnancy, her racially incorrect dream that she will one day be wealthy enough to buy fruit sliced by white people, or sexually transmitted diseases (she describes HPV as a monster that hides in a man’s body, but only goes “boo!” in a woman’s body), she does not do so in an attempt to shock. She is merely pointing out the simple yet for many not obvious fact that women, just like men, are beings with quite ordinary human needs. 85%

Mia Madre (2015)

Despite having a serious central theme, Moretti’s two previous films, The Caiman and We Have a Pope, were close to satirical comedies in terms of genre. Conversely, My Mother is a very sensitive and only exceptionally humorous study of coping with one’s own mortality and the loss of a loved one. How can we continue in our own lives when we are left behind by the person to whom we owe our very existence and whom we have accepted as an important part of our world? Moretti thematically returns to his most famous film, The Son’s Room, while also adding his favourite motif of reflecting on his own craft through the female protagonist’s profession. ___ Shooting a political drama about a strike by factory workers serves as a distraction for Margherita. She runs away from a very serious event in her life (the inevitable death of her mother) to an event that she has elevated to a matter of importance in her own eyes. Displacing death with art was clearly a tactic that Moretti had used himself when his own mother died during the making of We Have a Pope. It is as if he wanted to reconstruct this situation in his new film by dramatic means and find within it both meaning and a lesson for his future life. ___ The core of the story should obviously be the relationship between Margherita, Giovanni and Ada. This can also be seen from the sketch-like depiction of the film crew composed of entertaining caricatures without greater depth. The superficiality of the film’s storyline with moments of somewhat forced humour contrasts so sharply with the psychological depiction of the family that we get the feeling that we are watching two incongruous films. ___ Dream sequences and flashbacks comprise an equally jarring element of this otherwise realistic and linearly plotted film. This apparently involved creative intent and a means of highlighting the conflict between one’s personal and professional lives. However, the sudden changes in tone prevent us from fully appreciating the psychological authenticity, emotional sincerity and economy of expression with which Moretti is able to depict the inner experiences of his characters, in whose case he gets by with revealing details and unobtrusive staging of astutely observed situations. ___ The film’s style does not draw unnecessary attention to itself and is fully subordinated to the comprehensibility of the characters’ dialogue and feelings. Despite the melodramatic nature of the plot, the actors do not resort to theatrical gestures when expressing themselves. With the exception of Torturro, whose performance is guided by the screenplay, their acting is as subdued as the whole film itself. My Mother is a placidly flowing contemplation of one’s attitude toward death and a stimulating humanistic drama packed with grief, but also containing uplifting moments of human understanding. 65%

Tomb Raider (2018)

Next to Wonder Woman, Lara comes across as a poor relation (perhaps producers perceive gamers as a weaker audience than comic-book readers). Tomb Raider offers a total of four environments (London, Hong Kong, an island, a tomb), no spectacular action scenes with the exception of the waterfall, and basically just one (rising) Hollywood star. In the context of the efforts to create a full-fledged action heroine, however, it represents a small degree of progress. Lara Croft is absolutely believable as portrayed by Alicia Vikander, who has natural acting ability. The pair of screenwriters (Geneva Robertson-Dworet also wrote Captain Marvel) did not engage in experimentation, instead offering a traditional origin story that clearly introduces non-gamers to the world of Tomb Raider and gives gamers a satisfying portion of backstory and a number of direct quotes from the game. Lara is introduced to us by the pair of opening action scenes as a woman who does not excel through tremendous physical strength, but through her ability to come up with clever solutions to problems. In both cases, she fails anyway. It is only after she actively resolves here “daddy issues” that she becomes a strong and self-confident (though not fearless), yet relatively credibly vulnerable action heroine. One gets the impression she has always had all of her presented abilities, some of which she owes to her father (problem-solving, archery), but that she only lacked inner balance, as she had no father figure in her life. In this respect, this outwardly progressive film is terribly traditionalist (actually in a similar manner as The Last Jedi – substitute Dominic West for Mark Hamill and you get the middle part of the film). However, the family storyline, primarily presented through flashbacks at first, is incorporated well into the main narrative, driving the plot and explaining the heroine’s motivations, while helping to bridge longer periods of time when the characters are moved to a different location. When it comes to any given scene’s contribution to the narrative, Tomb Raider is above reproach. There are almost no dead spots when we would lose interest in what happens next (Nick Frost’s cameo could have been shorter, or deleted). Everything is nicely connected and all of the parts fit together, though perhaps too smoothly and straightforwardly. The action scenes are sufficiently diverse and boldly reminiscent of the video game (and demonstrate how Lara improves herself in individual areas – hand-to-hand fighting, escaping from pursuers, jumping long distances) and the pace does not slacken. Just as in The Wave, Uthaug displays flawless mastery of his craft and knowledge of the principles of classic Hollywood storytelling. Within the action genre, that is not a bad thing at all, but I hope that the sequel, for which the conclusion of this film somewhat long-windedly and too obviously lays the groundwork, will not be as exceedingly cautious. 65%

Risk (2016)

Like Citizenfour, Risk is shot as a paranoid thriller that plays out in an atmosphere of rising mistrust. The danger here does not come only from the outside. Not even people from the immediate vicinity can be trusted. As the director confides to us in additionally recorded off-screen commentary (the original cut sounded less critical toward Assange), she does not have a good feeling about the main object of her interest – a sexual predator who may have contributed to Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential election by leaking information. Assange is definitely a less transparent figure than Snowden, which is also reflected in the structure of the documentary, which itself is less focused (and gripping) than Citizenfour, imbued with the director’s doubts. Assange is styled into the role of Jason Bourne (a bizarre scene involving a motorcycle ride), whose main weapon is information and who uses self-centred philosophical monologues instead of punches as a means of defence. He almost seems to enjoy the fact that he is being watched, thanks to which he can present himself as a person who is so influential that it is beneath him to address his personal life in the media (an interview with an intoxicated Lady Gaga, who disinterestedly listens to him talk about all of the people out to get him). But are global issues a reason to ignore local issues? Is it possible to trust a person who calls for maximum transparency, but equivocates when it comes to his own actions? I don’t think so. Besides presenting a portrait of a highly self-contradictory figure, Risk secondarily demonstrates why it is so difficult for women to assert themselves in the field of IT, where the main say is had by men with bloated egos, such as Assange and Appelbaum, who occasionally utter an inappropriate sexist remark (to which the women present react with embarrassed looks) and are not averse to abusing their own power. It seems peculiar to me that a film filled with doubts about who can be trusted and who actually acts properly does not offer any definitive answer and ends with a big question mark. From this perspective, it is an accurate reflection of the chaotic nature of the age in which we live and of which people like Julian Assange are emblematic. 75%

Mistress America (2015)

“There’s nothing I don’t know about myself. That’s why I can’t do therapy.” Mistress America is the latest and so far probably best of Baumbach’s indie comedies about talkative New York intellectuals with artistic ambitions whose self-confidence far exceeds their actual abilities. Irresistible for some and unbearable for others, Brooke ceaselessly spits out words in an effort to convince those around her that she is the personification of the ideal that every female New York hipster wants to achieve. Funny, popular, independent and successful, she is her own woman. She is knowledgeable about current cultural and technological trends, though she is a bit disdainful of them at the same time. This is how she presents herself in her artificial world on social networks, and it is also how the inexperienced Tracy sees her. In reality, she has neither friends nor the patience to see a project through to the end, and her seemingly inexhaustible energy is merely well-disguised hysteria. She is surprisingly confronted with harsh reality thanks to Tracy, who misuses her as a satisfying source of literary inspiration and, besides her character traits (self-confidence bordering on arrogance), impertinently “borrows” her life story. The merciless uncovering of the true nature of the outwardly flawless Brooke places Mistress America in the line of films and series like Girls, setting a mirror in front of the generation that should soon be running society but still lacks most of the prerequisites to do that (e.g. the ability to independently choose the right pasta). At the same time, the bitter undertones do not prevent us from enjoying the refined visual aspect, the excellent placement of the actors in space (which in several settings is created in part by the characters’ voices in addition to their movements) and the truly funny one-liners that the characters fire at each other at the frenzied pace of the best screwball comedies. The dialogue has an almost musical rhythm. In addition to words, Baumbach uses, for example, Tracy’s sabre throwing and a pair of cute cats to get to the point. One breathless scene leads to the next and basically the film constantly escalates through the first half, so we don’t get a chance to really get to know the characters. The demolition of dreamed-of worlds and the casting off of masks, for which we are prepared by the narrator’s commentary on how the world began to turn against Meadow (Brooke’s fictional alter ego), happens only during the narratively and beautifully concise developmental act in Greenwich. As the characters lose their illusions about themselves, the ode to female friendship transforms into a scathing portrait of a generation growing up in a world that offers so many possibilities that it is almost impossible to be yourself, to be original and not imitate someone else. Neither the easing of the rhythm nor the sudden change in the tone of the narrative is a penalty for this. Though rarely consistent, Mistress America is in every respect a well-made comedy that deserves significantly more attention than the films of the same genre and the same country of origin with which distributors commonly contaminate cinemas. 85%

Los archivos del Pentágono (2017)

I expected The Post to be a good movie. I did not expect it to be nearly flawless. There is much to be admired in it, especially knowing that the project was announced in March 2017 and was in cinemas by December, but what I enjoyed the most was how various subworlds (family and work, men and women, friends and colleagues, The Washington Post and The New York Times) constantly collide in the film at the level of both narrative and style, which adds dynamics and layering to a film that is largely based on a few people in a room discussing huge amounts of data or deciding on something essential. ___ The differences between the worlds among which the characters move are made clear thanks especially to Kamiński’s camerawork and the directorial control of the space in front of the camera. There is almost no shot that does not convey something through its composition, the placement of the actors, the inevitability with which the characters dominate the given setting (Kay is more comfortable at home, Ben in the newsroom), the contrast of events in the foreground and background, the speed and direction of camera movements.... At the same time, the film never comes across as didactic, but rather as something entirely natural and organic. For example, granddaughters running in the garden in the background during a work conversation between Ben and Kay, and the camera’s sharp glance at a portrait of the female protagonist’s father hanging on a column that she walks past gives the scenes extraordinary emotional depth without descending into sentimentality and slowing down the narrative. ___ Even though we are subjected to a constant flow of information, especially in the first half, which covers several days (in the second half, the field of possibilities of how the narrative can develop further is significantly narrowed and mostly takes place in a single day, thus making it even more suspenseful), you can still find your bearings in the film and know where it is headed thanks to the clarity with which it was made. ___ Thematically, The Post is a prequel to All the President’s Men on the one hand and, on the other hand, another Spielberg story about an absent father, a family (due mainly to which a night-time conversation with the daughter is important, though for many that will be irritating proof that Spielberg can’t handle endings) and the occasional necessity of bending certain rules in order to keep democracy alive. For only the third time in a Spielberg film (after The Color Purple and The BFG), there is at the centre of events a female protagonist around which all storylines and motifs – the fight with the government, social expectations, self-confidence – converge (initially intersecting roughly halfway through the film, until which time Kay does not become involved in the newspaper’s contents). ___ The Post is thus relevant not only as a critique of unlimited power and defence of freedom of the press, but also as a story about a woman who has to risk everything in order to show men that she is just as capable as they are and to thus achieve, at the individual level, the same freedom desired by newspapers to write without sanction about dubious government activities (the strongest scenes include those in which Meryl Streep finds herself surrounded by men who literally and figuratively prevent her from moving and to whom she first submits before gradually learning to stand up to them).___ Due to its seeming lack of action, Spielberg’s latest work will not be easy to follow particularly for non-American viewers (especially those who don’t pay attention to what the film conveys visually), but if you liked Lincoln, you should be very pleased with The Post, despite its being even less of a spectacle (the most epic scene depicts the printing and distribution of newspapers). 90%

madre! (2017)

Mother! is a very dark comedy of morals that degenerates into a surreal apocalyptic horror flick. First through hints and then increasingly explicitly, Aronofsky’s film makes it clear that we are not watching a realistic story. The idea that it will be a variation on Repulsion (1965) or Rosemary's Baby (1968), i.e. a domestic horror movie about a paranoid female protagonist, holds together for roughly the first hour. Then the film definitively abandons the moral, logical and any other norms that apply in our current world. The characters’ actions can no longer be explained based on any psychological parameter, there are no rationally legitimate relationships between events, and the laws of physics cease to apply. The subtext becomes the main text and it is impossible to come to an interpretation that is anything other than allegorical, unlike the above-mentioned Roman Polanski films, which until the end keep us in a state of uncertainty as to whether we are only watching the personified fragments of the protagonist’s disturbed mind. In attempting to come to a reading that is more grounded in reality, the film’s structure would collapse. However, Mother! does not base its narrative on uncertainty and unanswered questions. Nor does it try to encourage viewers to think about what has been left unsaid. As is his habit, Aronofsky instead shamelessly shoves his “big ideas” is our faces. Watching the film is an uncomfortable experience not because we would be groping for the message that it is conveying, but because we know (and see) more than we want. Sometimes it is necessary to attack all of the senses. Thanks to our physical attachment to the main character (the camera practically never wavers from her point of view), we sympathise with her, experience her physical suffering and understand both her growing frustration and her final act of defiance. In most of his films, Aronofsky works with a similarly aggressive visual style, for which he is often ranked among the biggest posers of contemporary American cinema, but for the first time in mother!, he clearly found appropriate material on which to use it. We can see the choice of the “story of all stories” as the basis for the narrative as a manifestation of a lack of judgment. However, we can also see it as a middle finger raised at critics who had previously blamed Aronofsky for the efforts of numerous midcult artists to address the problems of the entire universe with trite brevity. Mother! goes back to the beginning of life on Earth and, at the same time, ostentatiously flaunts its own banality. It doesn’t pretend to be high-brow art that we should long contemplate. A bit in the spirit of the “theatre of cruelty”, it is rather a naked attempt to draw attention, by any available means of expression, to the crisis in which humanity has found itself due to unjust social conditions and people’s selfishness, disinterest, hypocrisy, dismissiveness and complacency. It is a desperate and, in its ingenuousness, extraordinarily authentic cry, not a genial request. Perhaps you will find it offensive, or maybe you’ll laugh at it or it will make you sick, but it if doesn’t leave you indifferent, it has served its purpose. 90%