Reseñas (935)

Gloria (2013)

With its slapdash style, reasonably light (but not lightening) tone and vivid acting, Gloria is a simple and straightforward yet unusually long-resonating film. Gloria’s search for someone who would love her and live with her to the fullest instead of slowly growing old doesn’t go in unexpected directions and doesn’t try to shock us (the amusing femme fatale interlude comes across as subversive, especially due to the fact that, contrary to custom, a woman indulges in the game instead of a man). Secondary meanings that deepen the seemingly one-dimensional narrative emerge from the protagonist’s interaction with the mise-en-scène, whether that involves a pleasantly morbid confrontation with a dancing skeleton (which unexpectedly returns Gloria’s gaze) or a revealing shot of a nude Gloria next to a nude tomcat, a creature that hides nothing and from which the woman has nothing to hide either (it seems living with Rodolf forestalls the option of going to the market with her skin uninhibited). If Gloria displays tremendous courage in anything, it is not in flaunting her nudity or looking for love after 50. She has my admiration mainly for not being afraid of a positive impression, which is not forced, but is completely in line with the protagonists refocusing of attention from the outside to the inside. Thanks to Paulina Garcia’s spontaneous performance and the fact that she doesn’t try to push major themes to the forefront and captivate the audience with formal embellishments, I found the film much more believable than Baumbach’s Frances Ha, which now seems to me an immature, more eager-to-please and thus less natural version of something similar. 80%

Feliz día de tu muerte (2017)

This likable, silly guilty pleasure ranks among the Blumhouse’s best (over)productions. The film proves that it’s hard to keep a straight face with a time-loop narrative, even (and perhaps especially) in the case of a slasher flick whose repetitiveness turns Happy Death Day on its head. Death is followed by a do-over and a new start, so we’re entertained by the protagonist’s (the great Jessica Rothe) endless dying instead of fearing for her (though that comes up a few times, but it’s really not the main point of the film, or rather I wouldn’t blame it for not making you fearful enough). Thanks to that, the classic “whodunit” formula plays first fiddle together with the relationships between the characters and the transformation of the protagonist from being terribly oblivious into a rather fine girl (so you can see the deep message in that – when confronted with one’s own mortality, one starts to behave sensibly). In the end, Happy Death Day is pretty much a high-school comedy in which the protagonist dies a few times on the way to finding love and self-confidence. Though the story outwardly starts from the beginning, the film holds together excellently thanks to its adherence to the classic narrative structure. Each successive variant is a response to those that came before it, we learn new information (or rather individual suspects are eliminated), the protagonist undergoes a transformation, thus giving the impression of smooth development. At the moment when the formula could become boring, a change occurs that reflects the culmination of Tree's transformation from prey to hunter. Yes, it’s a goof that doesn’t take itself seriously and quickly fades from memory, but it is definitely not a dumb movie. 70%

El sacrificio de un ciervo sagrado (2017)

Saw for intellectuals. The Killing of a Sacred Deer is a cruel, disturbing and, in filmmaking terms, precise morality tale and perhaps even class satire (rich people destroy the lives of the poor and refuse to accept responsibility for it), but I found its second half to be monotonous in terms of both the characters’ suffering and style (slow dolly shots, overhead shots, close-ups of faces, unpleasant atonal music, over and over again). I understand that the mechanical nature of the structure and the acting is part of the director’s malevolent concept (forget about gradation or catharsis), but it deprives the film of dramatic tension and gives the impression that it doesn’t develop along with the characters, while also weakening the message. I didn’t get the impression that the film had anything else to say after the central dilemma had been revealed (which was possibly why Mirka Spáčilová providentially left the press screening after the scene in which Farrell forces a donut on his son). Instead, it distances itself from reality and thus diminishes the power of its message. The similarity to Kubrick or Haneke is mainly external, not in the effect that the film has on the viewer. 70%

Thor: Ragnarok (2017)

“Darling, you have no idea what's possible.” I hope Waititi's next film is an adaptation of the Robot Unicorn Attack flash game, because this wasn’t far from it. Though the New Zealander with a fondness for pineapple-print shirts didn't write the screenplay, I think he deserves credit for how colourful, nutty and stylistically diverse the whole film is. In just the first few minutes, we become witnesses to the protagonist’s self-ironic conversation with a skeleton, a variation on the “Look at my shit” scene from Spring Breakers and a parody of the theatrical, statuesque nature of Thor’s first solo movie. I actually found it regrettable that Waititi had to stick to the Marvel canon and expand the MCU (the scene with Strange was a bit superfluous) and couldn’t construct the whole film as a laid-back buddy movie in which Thor’s patience is gradually tested by Loki, a talking pile of rocks who wants to start a revolution, a perpetually plastered Valkyrie, and an egghead with seven doctorates and a problem with self-control. The characters and their sparkling dialogue draw more attention to themselves than another generic plot with a goddess of death who wants to unleash hell because she has daddy issues. Fortunately, the narrative structure is partially adapted to this. After the main storyline gets rolling, the protagonist is plunged into a world where he has to deal with completely different concerns, so rectifying the situation on Asgard, of which Thor is informed only through hearsay, has to be delayed. On top of that, the protagonist is merely pulled along by fate (or by the Hulk) more than once and cannot freely make decisions; things happen without his input. The subversiveness of this approach, which turns the whole superhero concept on its head, culminates in the climax, when the problem is resolved differently (and by someone else) than you would expect. When you add the actors enjoying their roles (Tessa Thompson and Jeff Goldblum are particularly superb), the arcade-inspired action scenes and the cleverly dumb humour to the methodical rejection (or, as the case may be, commenting on and mocking) of the rules of the game, you get a movie that will either irritate you with its refusal to take anything seriously or thrill you as the most entertaining Marvel movie ever. For me, it was the latter. 85%

Bone Tomahawk (2015)

It’s nice to come across a genre film that takes its time, lets the shots fade out and, instead of quickly satisfying viewers, slowly builds the atmosphere and the depiction of the characters. Thanks also to the patient and precise work with the mise-en-scène and the old-school linear narrative, it’s easy in the first hour to fall under the impression that you’re watching a classic western. In fact, Bone Tomahawk is a post-classic western combined with a cannibal horror movie (at the same time, the second half of the film can be seen as a subverted variation on hixploitation). Conducting themselves with the straightforwardness of cowboys, the men, one of whom is a cripple and the other a purblind widower, are branded as idiots by the self-sufficient female protagonist, while the ignorant attitude towards native culture has bloody consequences, and the theory of the frontier (between wilderness and civilisation) is not only taken to hellish extremes, but can also be related to the genre bipolarity of the film, which quite thought-provokingly explores the overlaps of horror movies and westerns (fear of strangers, the arrogance of the powerful white man). Though the ending doesn’t provide the satisfaction that I would have expected based on the care taken in the preceding two hours, Bone Tomahawk is still, together with The Hateful Eight, the best western updated for the troubled times in which we live, and by drawing from the exploitation tradition, it is far wittier and honest than The Revenant.

En realidad, nunca estuviste aquí (2017)

With numerous omissions, silences and hints, You Were Never Really Here is a very distinctive revenge flick that explains some things only after the fact (when snippets of flashbacks are put into a broader context) and others not at all. (The narrative, with dynamic cuts in the middle of the action, is highly compressed partly due to the need to shorten it – the budget was slashed significantly in the course of filming.) Ramsay does not in any way romanticise her taciturn tough guy with his numerous wounds on both his body and soul. For her, Joe is a wounded animal (which is aided by the respect-inspiring Joaquin Phoenix, who delivers another full-throttle performance following his turn in The Master) whose actions are unpredictable from one moment to the next. Together with compassion, he inspires fear and you definitely don’t feel very safe during the hour and a half that you spend in his company. The violence, which comes suddenly and is framed without dark humour or ironic exaggeration, is truly painful and unpleasant here, not only because the protagonist’s weapon of choice is a hammer. As the aggression shifts from the level of mere association (bloody handkerchiefs, crushing a piece of candy between his fingers) to something very concrete and very brutal (though the director continues to work brilliantly with evocative sounds and the off-screen space, leaving a lot to the imagination), the sense of danger becomes unbearably acute. The action scenes best demonstrate how the director methodically denies us the genre pleasure of the protagonist’s cleanly done work. We see one of the key bits of action only in static black-and-white shots from a security camera, the nondiegetic music and voices emanating from the television distract us from the brutal fight, and the “grand” climax is highly unsatisfying in terms of (not) fulfilling the conventions of the action genre. So much suffering and despair line the path to redemption that every partial success brings forth bitterness and deepening frustration instead of catharsis. It is simply impossible to enjoy the film, which makes it irritating and fascinating at the same time. Lynne Ramsay has made a stylistically diverse “feel bad” genre deconstruction (like in The American and Point Blank, meanings are communicated through style rather than through the words and actions of the characters), switching abruptly between raw realism, dream sequences and hypnotic intermezzos in which Jonny Greenwood’s aggressive music becomes the focal point. After the film had ended, I wasn’t entirely sure about what happened to whom in the story, what was a bad dream and what was an even worse reality. Like at the end of Good Time, however, I knew I wasn’t going to see anything comparably deviant in the cinema. But I wouldn't be surprised if this admirable exercise in narrative brevity is simply an underdeveloped genre experiment by a director who wasn’t exactly sure what she wanted to make. Perhaps she didn’t know (and the last act was really made up as she went along), but for me, this was one of the most intense cinematic experiences of the year. 85%.

Spielberg (2017) (telepelícula)

Formalistically, Spielberg is a conventional documentary interspersing talking heads with scenes from films and the production thereof and offering a chronological overview of Spielberg's filmography. This is expanded on the vertical axis with a look into his childhood. Despite the extensive runtime, it falls far short of covering all of his films. Unsurprisingly, the films that received a largely positive reception at the time of their release predominate (there is no mention of Always, Hook, The Lost World or Amistad) and reflect the themes that, at least according to the documentary’s creator, are determinative for Spielberg (democracy in Lincoln, the father-son relationship in Catch Me If You Can, the struggle against terrorism in Munich). ___ Lacy chose a similar interpretive key as Molly Haskell’s recently published Spielberg biography, only less critical: She explains the choice and handling of certain themes through the influences that shaped Spielberg’s childhood (fear of the unknown, the divorce of his parents, his Jewish origins). Thanks to this, she succeeds in conveying Spielberg’s personal life without losing sight of the films that comprise the main reason for the documentary. ___ The tone is predominantly adulatory (with the exception of The Color Purple, which is referred to as “fake and Disney-esque”), but without pathos and unnecessary repetition of previously spoken words of praise (for example, we don’t hear over and over again that Spielberg is a great father who knows how to direct children). Furthermore, most of the speaking is done by Spielberg himself, who rather than talking about how he used to pick up girls in his youth (we learn about that from Brian De Palma), talks about the structure of the story and the technical handling of specific scenes, and his words basically confirm what most of those involved in the film say about him (Martin Scorsese and Janet Maslin offer the most insightful observations) – he has extraordinary storytelling talent and the ability to convey meaning through imagery, and he almost instinctively understands how to approach a scene in order to make it both comprehensible and attractive for the viewer. ___ If you, as a Spielberg fan, have seen the “making of” most of his films or Richard Schickel’s documentary about him, you won't learn much new from Spielberg, but you will be reminded of what makes the man unique, thanks to people who are a pleasure to listen to. Like me, you will also most probably get goosebumps during the segments showing his films’ famous moments underscored with John Williams’s music. In the context of the chosen concept and the focus on a broader audience, this is a satisfying work, but if someone in the future makes a more formalistically or interpretively daring documentary about the master, I would not be upset about that. 80%

El juego de Gerald (2017)

The first half Gerald’s Game plays out promisingly with just two well-matched actors and a dog (a similar setup as in The Mountain Between Us, which is currently in cinemas) in one room, an unpleasant situation and a few objects that could potentially resolve it. There are plenty of cuts and changes of perspective to hold our attention, the uncertainty of what is real and what is only imagined (in which the film is a more sophisticated variation on torture porn – it’s not just about physical pain, but also about holding on to one’s sanity). The presentation of the female protagonist’s train of thought is handled more elegantly than in, for example, 127 Hours with its affected flashbacks. I consider the flashbacks, which first appear after roughly fifty minutes, to be the film’s main stumbling block. The heretofore concentrated narrative, with its strictly limited number of ways to continue the game, loses traction and gets bogged down in pseudo-psychological explanations for Jessie’s difficulties with men. This is King’s favourite abusive cliché, with which he works in It, for example, and which is based on the rather questionable belief that in order for a woman to discover her inner strength, she must first suffer terribly. Cutting out the flashbacks and the very awkwardly appended emancipatory afterword could turn this into a brisk low-budget surprise that has no need to complicate a simple initial idea with lengthy explanations. At the same time, however, I understand that it is also a service to King’s fans, who will most likely appreciate this self-destructive fidelity to the source material. 65%

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

In addition to a portion of hate, this review contains SPOILERS. The most notable thing remembered the day after viewing: Ryan Gosling had a really cool coat; I wouldn’t mind having one for myself in the winter. In the context of current Hollywood production, Blade Runner 2049 is indisputably an unusual film (in a way similar to Spectre). The characters, ideas and atmosphere are more important for it than the plot. The main protagonist does not play such an important role in the story as he (and we along with him) has long believed, which reinforces the dominant feeling of existential angst that comes from the impossibility of holding one’s fate firmly in one’s own hands. Most of the scenes begin a bit early and end a little later than is necessary to convey the essential information. Other scenes are of negligible importance to the story and serve mainly to evoke a specific atmosphere or to fill out the fictional world. (The rhythmising of the narrative by means of the deaths of the female characters can also be considered an original idea; in the final act, one dies every ten minutes, which is more indicative of the screenwriters’ lack of feeling than of their storytelling abilities.) The problem is that all of this is held together by a stylistically dull (the only interesting scene is the one in the bar in which Ford slaps Gosling) and straightforward melodramatic story about a son looking for his father (with the help of a wooden horse) and a father looking for his daughter (the final sign of class revolution, corresponding in its simplicity to a young adult novel that is better left unmentioned), and the whole film is basically much more predictable, literal and generic than it thinks it is and its pompous treatment would suggest (see the poster for the most essential revelation). Like the rest of Villeneuve’s work, Blade Runner 2049 confirms that a film with actors who spend the entire time acting as if someone has taken their favourite toy away from them (which is not too far from the truth in the case of Gosling’s character) and filmed in long shots accompanied by atmospheric background music will seem serious and important, but only on the surface. Whereas Scott’s film was thought-provoking with its abundance of things left unsaid, in this new treatment, the characters take care of all the philosophising for the viewer, expressing themselves in stilted, monosyllabic sentences. We can’t help but marvel at how beautifully the whole thing is designed (the sound design, at least, is worthy of an Oscar), but a coffee-table book with photos of the artwork would serve the purpose just as well as a nearly three-hour movie. I’m quite worried that Villeneuve’s Dune will be the same thing in pale blue (or orange). 65%.

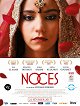

La boda (2016)

The opening shot, which presents to us the bare facts without equivocation as the main female protagonist conducts an “admission interview” at an abortion clinic, is likably bold and matter-of-fact. The rest of the film is neither. A Wedding tells a clichéd story about religious traditions that – especially for men – are more important than individual happiness. It does so in a not very economical, but very predictable and simple manner (just in case we somehow don’t understand from their life stories, two female characters carry on a dialogue about how difficult it is for a woman in a family clinging to tradition). The perspective of the parents and the brother is taken into account not so that we would have greater understanding for them (as in the recent The Big Sick, for example), but so that we understand that they understood nothing and were more concerned about Záhira (I haven't seen such clumsy use of the “Chekhov’s Gun” principle in a long time). A Wedding merely insensitively asserts the stereotypical image of Muslims as religious dogmatists who resist women’s emancipation and progress in general tooth and nail. Last year's Hedi, for example, managed to make something special out of a similar narrative formula with a civil concept and political subtext. In Streker’s melodramatic film, which takes only extreme positions (hysterical father, grand speeches about the loss of honour, references to an ancient tragedy), only the excellent Lina El Arabi in the lead role comes across (and acts) naturally. Without her, it would be truly difficult for me to find a reason to attend A Wedding. 50%