Director:

Jacques RozierCámara:

René MathelinReparto:

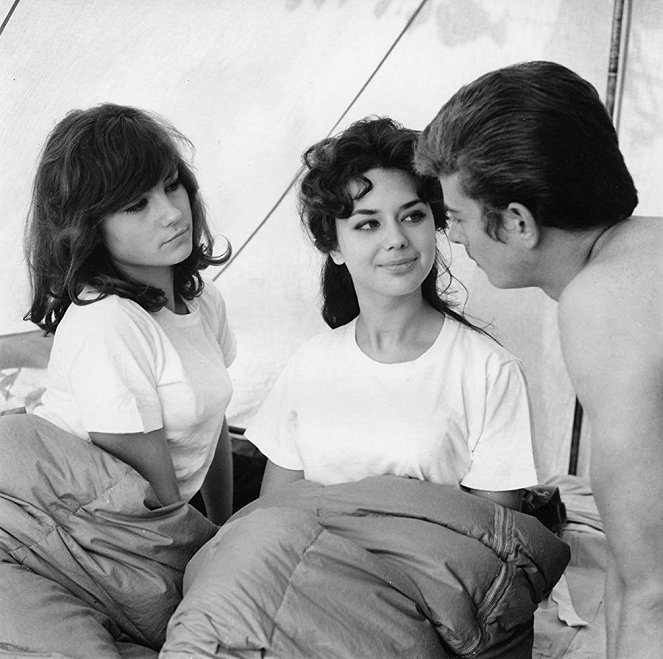

Maurice Garrel, Jean-Claude Brialy, Michel Piccoli, Robert Hirsch, Vittorio Caprioli, Marco Perrin, Jeanne Pérez, Pierre Frag, Edmond Ardisson (más)Sinopsis(1)

Michel plans one last fling before being sent to Algeria on military service. Only slowly does he realise that the girls he takes with him on holiday love him for who he is, not for what he pretends to be. (MUBI)

Reseñas (1)

Adieu Philippine, an intentionally aimless New Wave predecessor of George Lucas’s American Graffiti, will probably remain the only more significant work of Jacques Rozier. The film’s delayed premiere (due to the complicated editing of a tremendous amount of material, problems with funding, additionally shot scenes and the necessity of redoing poorly recorded pieces of dialogue) caused the film to be released to cinemas after interest in young French cinema had mostly dissipated. ___ The purpose of Rozier’s playful and seemingly improvised approach to directing is not to entertain, but to play with the form itself, though the narrative is intentionally and irritatingly broken up by means of various editing methods, including jump cuts and axial cuts (the numerous instances of montage techniques compelled Christian Metz to use Rozier’s film as a case study for his syntagmatic analysis). Sound, which is just as important as movement for Rozier’s musical grasp of rhythmisation, is paradoxically the main element in the editing that makes the film whole. ___ The jazz soundtrack, laid-back and rather episodic narration, the summer-holiday atmosphere and lack of serious conflict obscure the fact that the actual theme of the film is about something that is not explicitly expressed here (with the exception of the opening credits) – the end of innocence. The slower and practically plotless second half of the film is reminiscent of a long, reluctant farewell to youth, which is underscored by the last scene, an indirect expression of desire, so that at least this farewell will always endure. Other than in the opening credits, there is no mention of the war in Algeria, yet the idea of it is constantly present in the film (powerfully in, for example, the scene with the taciturn friend who has just returned from the war). Just as every scene “smells” of American culture, this is a means of distracting the masses. Because of its seeming hollowness, the film imitates the purpose of French consumerism at that time (most conspicuously apparent in moronic TV commercials), which also drew attention away from serious events, which thus at most became topics of conversation to fill the silence between the hors d’oeuvres and the main course. ___ Like the narrative, the protagonists are not focused on a particular goal. They merely kill time by playing games. They just want to have a good time all the time in order to push out thoughts of the future. They are interested in relationships, money and how they look (which is true especially of the two girls, who essentially lack any personality and are defined exclusively through their male counterparts). Thanks to its delayed release to cinemas, Adieu Philippine can be seen as a caustic commentary on the fate of the nouvelle vague (in both the sociological and cinematographic senses) – as the story of a group of carefree young people, some of whom never developed their talent and others who sold out. However, the film also lends itself to an opposite reading. If Rozier is ridiculing anyone, it is not the young protagonists (who, unlike Godard’s characters, are not passionate cinephiles), but the Italian producer, whose following of fashion trends is nothing more than commercially motivated posturing. In opposition to him stands spontaneous youth. Perhaps unproductive, but sincere. 60%

()

(menos)

(más)