Director:

Dagur KáriCámara:

Manuel Alberto ClaroMúsica:

SlowblowReparto:

Jakob Cedergren, Nicolas Bro, Tilly Scott Pedersen, Morten Suurballe, Bodil Jørgensen, Nicolaj Kopernikus, Anders Hove, Kristian Halken (más)Sinopsis(1)

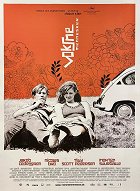

Daniel (Jakob Cedergren) is a graffiti artist who earns a living by spraying declarations of love on the walls of Copenhagen City. On the record, he has earned seven dollars for the past four years. People at the tax office are starting to get suspicious, in fact everybody – the police, the public transport system, his landlord – seems to be trying to track this young man down. But Daniel listens to The Well-Tempered Clavier on his headphones and drives through fire on his Fiat 500 without noticing it; he seems to work on a whole other frequency level than the rest of society. Daniel parks his Fiat in front of a bakery one day and walks out with a bakery girl (Tilly Scott Pedersen) who has been fired on the spot for being high on psychedelic mushrooms. Her name is Francesca but prefers to be called Franc.

Daniel gives Franc a lift home and falls in love with her. There is just one catch, his best friend Grandpa (Nicolas Bro) is in love with her too. Grandpa is a young man who represents everything that Daniel does not; he's a nerdish kind of guy and a know-it-all who has stuck to the rules all his life. When he loses the race for Franc's love, Grandpa decides to focus all his energy on being an official football referee: From now on the football pitch will be the place where he can fulfill his need for law and order. While Grandpa trains hard for his debut match, Daniel has fallen into hard times. At an improvised flea market, he realizes that the objects for sale are his own belongings. There is no way to bargain with the little girl in charge; she's the landlord's daughter and he's had just about enough of delayed payments, kicked Daniel out of his rented trailer and put his uncompromising little daughter in charge of selling all his stuff for compensations. Daniel doesn't know what hit him.

While looking for a new place to stay, he is caught red-handed at work and found guilty of graffiti sabotage. The Judge (Morten Suurballe) who hands down the sentence leads a very different life from Daniel. He's a father, a married man and responsible to the uttermost in his line of work. But by the time he crosses paths with Daniel, we've already come to realize that something is missing. The Judge doesn't sleep at night and goes through his daily routine like a ghost of his former self. A small twist of fate is enough to put him off the track – one day The Judge doesn't show up at work and checks into a hotel instead. At the same time, Grandpa has his debut as a referee on the football pitch. To his surprise, it turns out to be a women's match. This pulls the rug from under poor Grandpa and his debut turns into a humiliating fiasco. There is only one way for him to go from here and it is downhill: The great moralist downs a bottle of wine and decides to go downtown with his friend Tejs (Nicolaj Kopernikus) and systematically break the ten commandments, one by one. (texto oficial de la distribuidora)

(más)Reseñas (1)

*SPOILERS* The key to why Kári chose seemingly distant and only frame-related stories of the judge and the "association" may be in one seemingly unimportant detail, which the director "mysteriously" emphasized. It is a double scene with punch-outs of paper from a hole punch, which the desperate judge first sprinkles on himself, and a little further on, in the same activity, the outsider Daniel marks them as holes (after which he is corrected that these are punch-outs, that the holes are in the paper). This "psychoanalytic" detail quite faithfully captures the two opposing characters: the judge has everything, yet he still lacks something, something that uproots him and drives him into desperate solitude. Daniel has nothing and desires nothing, he deals with the system (the great other) with a complete passivity that has nothing to do with revolt, and much more with the misunderstanding that there is any "symbolic order" to which I am subordinate at all. Daniel's indifference to the object of desire and "rift" is, in fact, what allows him to be happy (his story conspicuously resembles the post-hippie poetics of Copenhagen's Cristiania district – it's no longer about rebellion, just a slightly shy parallel existence "next to" the great other, with the need to accept at least the general rules of responsibility). On the other hand, the judge, the lawyer and the representative of the order, is condemned to dissatisfaction and to spontaneous disappearance – there is no place for him either "in" or "next" to the system. Grown-up People is not so much about revolt as it is about the possibility of coexisting – I like its naïve silent ending in many ways. Even if he answers yes, he leaves the door ajar. At its core, it's another praise for the simpletons, but thanks to an excellent second line with a man who's disappeared, it keeps its feet on the ground and, unlike its protagonist, doesn't lose touch with reality.

()